Measles vaccines have saved millions of lives and dramatically reduced infection rates, prompting experts to push for global eradication. However, progress has stalled.

Delivering vaccines to every community in the world is essential if the disease is to be consigned to the history books. That means transporting and administering vaccines to the most remote and hard-to-reach places on earth where refrigeration, health infrastructure and trained health professionals may not be available.

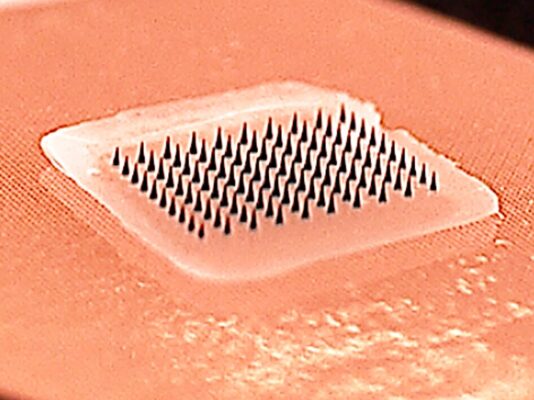

Reflecting the need for new thinking in the fight against measles, the Measles & Rubella Initiative last year cited ‘microarray patch vaccines’ as a potential ‘game-changer’ and said their development must be fast-tracked. The patches are like small sticking plasters with an array of microscopic projections that painlessly penetrate the skin and deliver the vaccine.

The potential to deliver vaccines in hard-to-reach areas without extensive refrigeration systems or highly-skilled workers is generating interest from international agencies and philanthropic organisations.

WHO has brought together technical experts to examine the technology and study how it could be used in Africa; the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has funded research; and the GAVI Vaccine alliance has drawn up a list of priority diseases that could be targeted with vaccine patches – including hepatitis B, human papillomavirus, rabies and flu.

However, measles remains the area of focus. The good news is, early trials are beginning to report results.

The big questions: are vaccine patches safe and do they work?

The short answer is yes.

A study published in The Lancet – the first to use microarray patches to vaccinate children – has shown that the method is safe and induces strong immune responses.

The research compared measles/rubella vaccine delivered by microarray patch with measles/rubella vaccine administered by conventional injection (with a needle and syringe).

The trial, which involved 45 adults (18-40 years old), 120 toddlers (15-18 months old) and 120 infants (9-10 months old) in The Gambia, found giving the microarray patch induced an immune response that was as strong as the response given by conventional injection.

Over 90% of infants were protected from measles and all infants were protected from rubella following a single dose of the vaccine given by the microarray patch. The measles and rubella vaccine used in the study has been given to many millions of children globally by conventional injection and is known to provide reliable protection.

The trial found no safety concerns with delivering the measles and rubella vaccine using a microarray patch.

Dr Ikechukwu Adigweme, from the Vaccines and Immunity Theme at MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM and co-author, welcomed the positive results: ‘We hope this is an important step in the march towards greater vaccine equity among disadvantaged populations.’

The trial had several limitations. As it was the first trial to use microarray patches to deliver vaccines to children, it had a small sample size and selected healthy adults, toddlers and infants. The researchers say larger trials of microarray patches are now being planned with broadly representative groups of children and infants. Results from these tests would inform decisions about whether to recommend the patches for widespread use in childhood vaccination programmes.

‘Although it’s early days, these are extremely promising results which have generated a lot of excitement,’ said Professor Ed Clarke, a paediatrician who leads the Vaccines and Immunity Theme at MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM and co-author. ‘They demonstrate for the first time that vaccines can be safely and effectively given to babies and young children using microarray patch technology.’

Measles vaccines are the highest priority for delivery using this approach, Prof Clarke noted, but the delivery of other vaccines using microarray patches is also now realistic. ‘Watch this space,’ he said.

Will vaccine patch technology finally deliver?

The idea of using patches to deliver vaccines has been around for well over a decade. In 2014, Vaccines Today reported that Australian engineer Prof Mark Kendall was promoting the technology, saying it could ‘change the world of vaccination’.

In 2017, we highlighted a study in The Lancet by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University which found self-administered patches were a safe and effective way to deliver flu vaccines. The scientists behind the paper said they planned to move on to bigger trials of polio, measles and rubella vaccines.

This month, Vaxxas, a company founded by Prof Kendall to commercialise the technology, received a $2 million grant from the US BARDA as part of its $50 million ‘Patch Forward Prize’.

Is this technology about to go mainstream? And if so, how long will it take before it finally has its moment?