More than 20,000 cases of monkeypox have been recorded in an outbreak that has taken public health experts by surprise. Monkeypox, which is often a mild illness but can be dangerous for people with compromised immune systems, has been found in most EU countries, as well as the United Kingdom and Switzerland, as well as dozens more outside Europe.

The surge in cases raises urgent questions for scientists and the public including:

- How do we stop monkeypox from spreading?

- Is there a monkeypox vaccine?

- Can monkeypox be treated?

First, the basics. Monkeypox is caused by a virus from the orthopox family of viruses. It is a close cousin of smallpox and cowpox. It causes blisters on the skin which fill with fluid. The virus is spread through close personal contact but does not spread in the air.

There is a limited number of specific antiviral therapies for monkeypox infection in certain patients, but most cases clear up without treatment. The sharp increase in case numbers, which may continue for some time as health authorities step up surveillance and testing, is an unwelcome challenge.

As the disease is relatively rare and is usually mild, it has not been a high priority for vaccine researchers. However, the similarities between smallpox and monkeypox mean that modern smallpox vaccines are likely to work well, according to Dr Peter English, an expert in communicable diseases and a member of the Vaccines Today Editorial Board.

‘Do we have a monkeypox vaccine? No, but orthopox viruses are similar enough that the immune system, once immunised against one of them, is likely to recognise another,’ he says. ‘This means that modern smallpox vaccines are extremely likely, in most cases, to prevent monkeypox infection.’

In fact, the similarity between the members of this viral family was instrumental in the development of Edward Jenner’s first smallpox vaccine. Jenner used material from a cowpox lesion to trigger immunity against smallpox. The rest is history.

Data from previous monkeypox outbreaks in Africa suggest the effectiveness of the current generation of smallpox vaccines may be at least 85%. Older people who have been vaccinated against smallpox are likely to have some level of protection against orthopox viruses, including monkeypox.

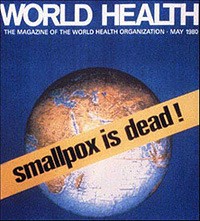

Smallpox has been eradicated

The smallpox vaccine has been hailed as one of the greatest achievements in the history of medicine, allowing experts to eradicate a human infectious disease for the first time. (Smallpox is still the only human virus to be wiped out; polio could be next on the list.)

Some modern smallpox vaccines are already licensed for use in preventing monkeypox; others have not been tested on smallpox as the disease is extinct. In July 2022, the European Medicines Agency extended the authorisation for an approved smallpox vaccine, allowing it to be used for the prevention of monkeypox. While it was not initially developed for this purpose, it is now, in effective, a monkeypox vaccine.

Stocks of the vaccines are being released to help fight the current monkeypox outbreak. The WHO has a stockpile of vaccines leftover from the smallpox eradication effort, along with millions more doses pledged by France, Germany, the UK, the US and New Zealand.

It is likely that lessons learned from wiping out smallpox 40 years ago could be applied today. This includes ‘ring vaccination’: an preventative measure which involves identifying and vaccinating those who may be at direct risk of exposure to an infected individual.

Mass vaccination is not seen as necessary given the nature of the virus and how is spreads. ‘Case investigation, contact tracing, isolation at home, will be your best bets,’ according to Rosamund Lewis who leads the WHO’s smallpox group.

Does chickenpox vaccine protect against monkeypox?

Another common question that arises as the public and scientists scramble to learn more about preventing monkeypox, is whether other existing vaccines might help. For example, if smallpox vaccines work against monkeypox, what about chickenpox vaccines?

There are several widely used vaccines against the herpes varicella-zoster virus (HVZ) which causes chickenpox. Unfortunately, these will not be effective against monkeypox as the HVZ virus is not part of the orthopoxvirus family. The names may suggest a link but that is where the similarities end.

For the moment, it seems that smallpox vaccines ‒ which have already delivered one of the defining achievements of public health ‒ are set to make a new contribution to disease prevention and control.