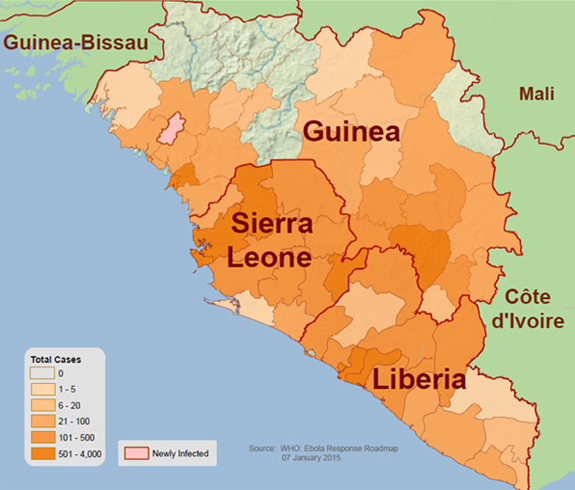

More than 8,000 people have died from Ebola in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, leaving 3,700 children orphaned.

More than 8,000 people have died from Ebola in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, leaving 3,700 children orphaned.

While these figures are making the headlines, the knock-on effects of the outbreak are now becoming clearer.

Hospitals are overcrowded and the health workforce has been hit hard by Ebola. Families are avoiding clinics for fear of catching the dreaded virus.

As a result, services for people with malaria have declined and more women are at risk of dying in childbirth because there are no hospital beds available. Immunisation rates against other infections have also fallen, meaning tens of thousands of children are left vulnerable to deadly diseases.

In Liberia, for example, monthly measles immunisation coverage against measles dropped from 71% in May 2014 to 55% in October.

This is leading to a surge in measles cases. Measles transmission traditionally peaks in West Africa between December and March but the current increase is beyond what would have been anticipated.

In Guinea, where a measles outbreak was declared in early 2014 – prior to the current Ebola epidemic – the number of confirmed measles cases increased almost fourfold, from 59 between January and December 2013 to 215 for the same period in 2014, according to WHO data.

In Sierra Leone, the figure tripled from 13 to 39 over the same period. In Liberia, which had reported no measles in 2013, four cases have been confirmed in Lofa County, one of the areas hardest hit by Ebola.

Read: Where are the Ebola vaccines?

Unicef, which is actively working to contain the Ebola outbreak, is seeking to restart stalled measles immunisation campaigns.

“Measles is a major killer of children that can easily be stopped through a safe and effective vaccine,” said Manuel Fontaine, UNICEF Regional Director for West and Central Africa. “But immunisation rates have dropped significantly, further threatening children’s lives.”

While vaccination campaigns that involve large crowds have been put on hold, UNICEF and partners are intensifying carefully guided routine immunisations to rapidly reduce the number of unimmunised children.

UNICEF says that as vaccinators venture out to provide lifesaving vaccines, they also help with the control of the Ebola outbreak.

“In compliance with infection prevention and control (IPC) procedures and WHO guidelines on immunisation in the context of an Ebola outbreak, UNICEF is providing not only vaccines, but also kits that include gloves and infrared thermometers for vaccinators,” UNICEF said in a statement.

Vaccinators are being trained on infection prevention and control measures, supervision during immunisation activities, and on how to conduct outreach sessions in areas which have not reported an Ebola case for 42 days.

Breaking the cycle of Ebola transmission and improving health services, including vaccinations, must go hand in hand in order to defeat the virus and to prevent large-scale child deaths.

“The best way we can help children is by stopping Ebola, while at the same time strengthening health systems,” said Manuel Fontaine. “We need to restore faith in the health system and offer communities regular opportunities for their children to get the vaccines they need to stay healthy.”

“Vaccinators and other health workers who are in the frontline need to feel protected so they can deliver life-saving interventions in the context of Ebola,” Fontaine added.