A coronavirus, apparently originating in animals before spreading to humans, causing severe respiratory illness. It may sound like a familiar story but it takes a very different turn to the one that led to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

- MERS-CoV was first identified in 2012 ‒ it is caused by a coronavirus

- Large outbreaks have been reported in Saudi Arabia and South Korea

- Symptoms include fever, cough and shortness of breath, as well as pneumonia and gastrointestinal problems in some patients

- MERS is transmitted from camels to humans and from human to human in close contact (such as a healthcare setting)

- MERS vaccine research helped to catalyse COVID-19 vaccine development ‒ now advances in COVID-19 vaccines may accelerate work on MERS vaccines

The story begins in Saudi Arabia in 2012 where doctors treating a patient who had presented with a mystery illness identified a new disease. It looked a little like the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) first seen in 2003, but the fatality rate turned out to be much higher.

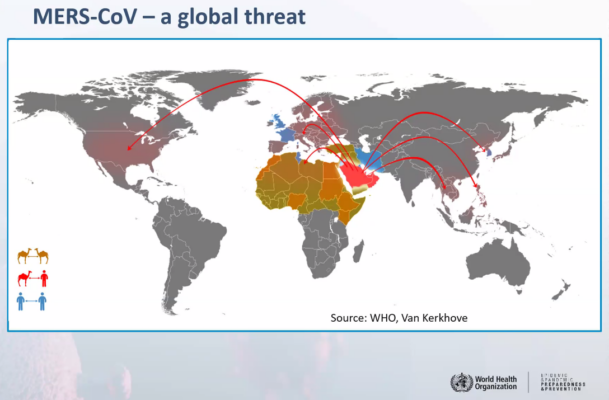

Concern grew as major outbreaks were recorded in Saudi Arabia and South Korea, with cases reported in multiple countries. The disease appears to come from dromedary camels and is most commonly found in regions with relatively high populations of camels. Person-to-person transmission has also been seen in the UK and France.

As well as posing a public health threat, outbreaks come at an economic cost. South Korea’s 2015 epidemic cost an estimated $8 billion (USD).

Where are we now?

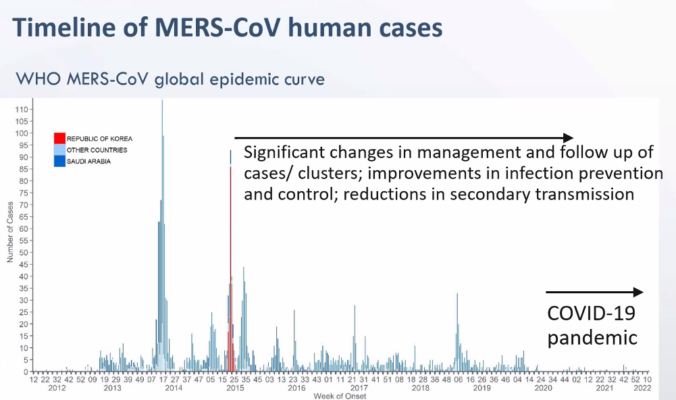

The good news is that cases appear to have fallen sharply over the past decade. And, where they occur, the size of the epidemics since 2015 have been small ‒ usually less than a dozen cases.

‘The peaks are getting smaller and smaller,’ Dr Sophie von Dobschuetze,WHO technical lead for MERS-CoV, told a webinar in late May 2023. ‘There has been a real dip since 2020.’ This may be the result of a combination of factors including cases going unreported, the impact of COVID-related social distancing measures, and possible cross-protection from COVID-19 vaccines or infection.

As there are no licensed treatments or vaccines, MERS remains a priority for the WHO, particularly given its potential to spread more widely. ‘The Risk of MERS-CoV emergence and spillover is higher in northern Africa and the Middle East,’ Dr von Dobschuetze said, adding that MERS should be considered in preparing for future pandemics.

In fact, just as countries that have responded to MERS outbreaks were well prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic, the COVID-19 response will inform preparations for outbreaks of MERS or other respiratory infections.

Dr Emad Almohammadi, Chief Officer for Communicable Diseases in Saudi Arabia, said his country’s One Health Approach ‒ which aims to address human, animal and environmental health in a holistic way, helped it to prepare.

‘We are using this experience and COVID-19 to prepare for the next pandemic,’ he said. ‘We have put in place stronger surveillance and data sharing, standards and audit of hospitals, training for community engagement, and improved lab capacity.’

The global lab network developed to manage MERS was used to rapidly sequence the SARS-CoV-2 virus ‒ a key step in developing vaccines and COVID-19 tests.

‘Years of vaccine development for MERS were quickly used for COVID-19,’ said Dr Maria Van Kerkhove, WHO lead on Emerging Diseases & Zoonoses, as well as being the COVID-19 Technical lead. ‘The work we’ve done for MERS, SARS-CoV-2, influenza and arboviruses will help us to prepare for the next pandemic ‒ whatever it may be.’

Preparation, not panic

Experts say there is no need to worry unduly about the threat of MERS. Instead, the goal of highlighting the risk of outbreaks, and experiences of Saudi Arabia and South Korea, is to boost overall pandemic preparedness.

Dr Sylvie Briand, Director of the Pandemic and Epidemic Diseases Department at the WHO, referred to some of the commentary on social media suggesting that the focus on MERS was a deliberate attempt to replace COVID-related anxiety. ‘That’s not the purpose at all,’ Dr Briand said. ‘MERS has been with us since 2012. If we know the risk well, we can manage it well. Preparedness counts.’