The highly-visible public activities of the four scientific societies behind the Calendar for Life gave fresh impetus to policy debates on how to improve vaccination rates and the health of the Italian population. In addition, there were ongoing concerns about outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles which kept immunisation in the headline. With the National Immunisation Plan due to expire, and the Calendar providing a clear template for a new approach, the time was ripe for change.

When the Ministry of Health established a task force to craft a new National Immunisation Plan, public health advocates had the wind at their back. Key officials in the health ministry and advisory committees were strong advocates of vaccination: Dr Ranieri Guerra, Chief Medical Officer and Director General at the Ministry of Health Directorate of Prevention; Professor Roberta Siliquini, President of the Higher Advisory Committee to the Ministry of Health (CSS); and Professor Walter Ricciardi, President of the National Institute of Health are all public health experts of international renown. “For our part, the National Institute of Health sounded the alarm three years ago when coverage for all recommended vaccines dropped below 95%,” says Prof Ricciardi. “It was time for a new Plan and we also wanted to take a lifelong approach; to introduce a strongly evidence-based calendar based on an analysis of the Italian epidemiological situation and international evidence.”

There was no lack of political will. Beatrice Lorenzin was appointed Minister of Health in April 2013 and was an outspoken advocate of vaccination for the Italian people – including her own family1. Lorenzin has provided stability at a time of considerable political turbulence. Three Italian Prime Ministers have been nominated since she became Minister of Health, each appointing her to the health portfolio. This stability and consistency ensured that the journey from theory to practice stayed on course.

With key decision-makers in the health system and academia embracing the Calendar for Life, it appeared the stars had aligned at just the right time for Italy to agree an innovative new immunisation programme in 2014. In reality, it would take two years of hard negotiation with regions and economic ministries before Italy’s new plan would be phased in.

From concept to reality: a long and winding road

Following a wide-ranging consultation process, a new immunisation plan was drafted and approved by the Ministry of Health. “Then the real fight began,” recalls Dr Ranieri Guerra. “The first challenge was to secure the agreement of regional authorities who must deliver the plan. Then came a long discussion about financial issues.”

Health officials made the public health – and economic – case to the economics officials and regional authorities. “We discussed the potential to prevent and reduce inappropriate admissions, lower spending on drugs and saving lives,” says Dr Guerra. “The Ministry of Economics viewed these as potential savings if the vaccine coverage targets are met. They were swayed by the case for disease prevention.”

Officials estimated that an addition €300 million euro would be required to fund the expanded plan – which recommended more vaccines than any of its predecessors. “The new plan almost doubles the number of contacts between the public and vaccination services,” says Prof Bonanni. “This helps to explain why it took two years to get approval.”

Prof Signorelli says most of the debates were about practical and financial issues: “From 2015 to the end of 2016 when the final version of the plan was agreed, the discussion was not about which vaccines to include but mainly about the resources needed to deliver it.” It was crucial, for example, that a formula was found for transferring national funds to the regions which would be used to support the rollout of new vaccine programmes.

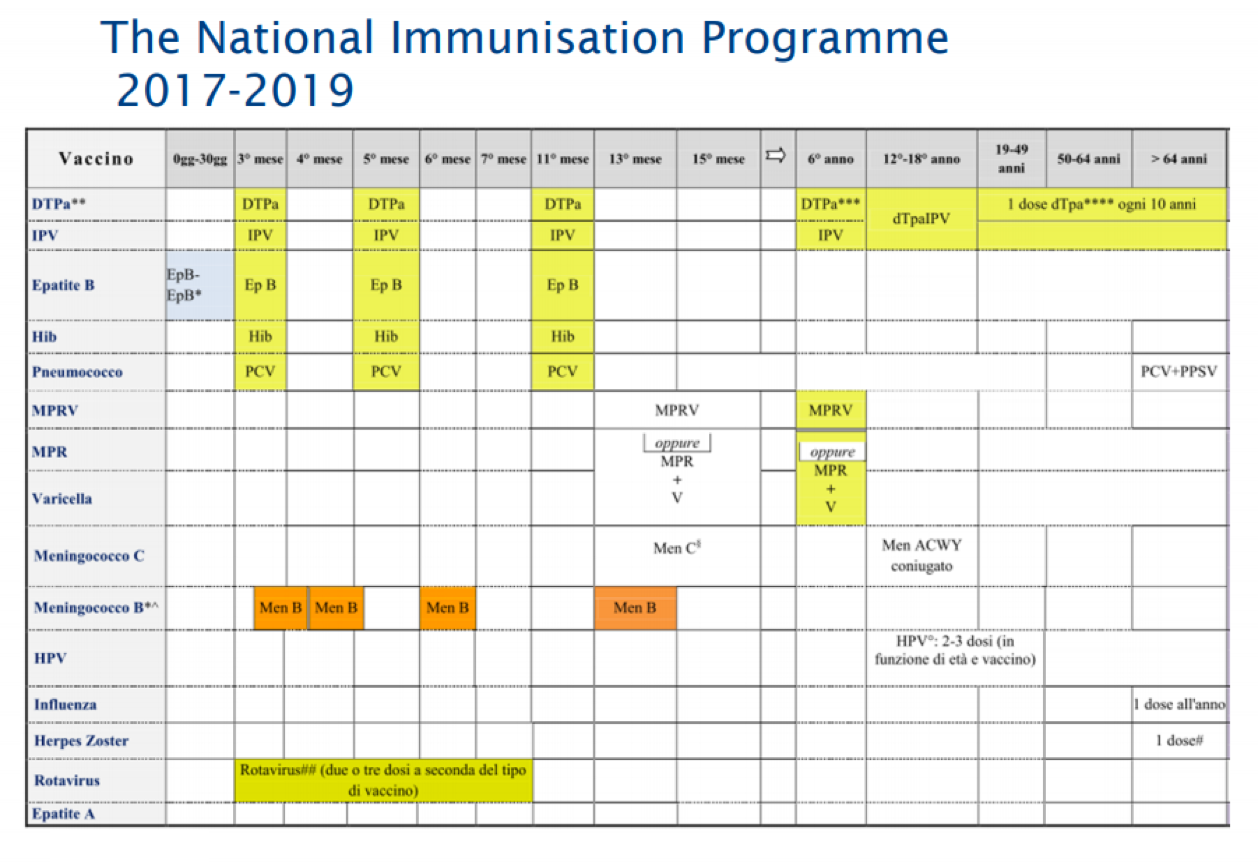

National Immunisation Programme 2017-2019

National Immunisation Programme 2017-2019

European momentum

Italy held the rotating six-month EU Presidency in the second half of 2014. This put Minister of Health Beatrice Lorenzin in the chair for meetings of EU Health Ministers. Using Italy’s position to set the agenda, Lorenzin and her officials proposed a joint statement on Vaccination as a Public Health Tool.

As Italy was in the midst of translating the Calendar for Life into a new national vaccination plan, the language of the Council Conclusions reflects Italy’s progressive thinking in this area.

The Conclusions invite EU Member States to ‘consider immunisation beyond infancy and early childhood by creating vaccination programmes with life-long approach’.

The document also calls for more research aimed at developing new vaccines and demonstrating the benefits of a life-course approach, the cost-effectiveness of immunisation and the effectiveness of risk communication, while at all times giving priority to citizens’ safety’.

The Council Conclusions added political momentum to the Italian Healthy Ministry’s domestic struggle to secure approval for the new immunisation plan.