In 2019, European public health researchers came together to explore a topic that is often overlooked: immunisation services in prison populations. As evidence was scarce, they had little to go on, aside from a small number of studies looking primarily at hepatitis B vaccination.

However, it was clear that prison populations had lower rates of vaccination than the general population, and that marginalised groups ‒ including migrants, ethnic minorities and people facing social deprivation ‒ are disproportionately represented in Europe’s prisons. Many people living in prisons had limited access to healthcare in general and low trust in authorities.

Key points

- Until the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination in prisons received little attention

- People in prisons often have lower vaccination rates than the general population

- Poor access to services and low levels of trust affect vaccine uptake

- Lessons from COVID-19 vaccination can be applied to flu vaccination

- Researchers see opportunities to deliver cancer-preventing vaccines, such as hepatitis B and HPV vaccines, to people in prisons

The researchers devised a plan to study and improve immunisation services in prisons, securing EU funding for a collaboration between nine centres. The RISE-Vac project was ready to launch in six countries when COVID-19 arrived, changing how people think about prison as a setting for vaccination. Prisons, often crowded and home to people with complex health needs, were seen as high-risk venues for COVID transmission. Suddenly, prison health was on the agenda like never before.

Building an evidence base

While prison was identified as a ‘setting of interest’ in the WHO’s 2016 viral hepatitis elimination strategy ‒ as people in prison are disproportionately affected by hepatitis B and hepatitis C ‒ other vaccine-preventable diseases were not a high priority.

‘Very little attention was paid to vaccination in prisons before the pandemic,’ explains Dr Lara Tavoschi of the University of Pisa who leads the RISE-Vac project. ‘We set out to develop evidence in several European countries and then incorporated COVID-19 vaccination into our work. But our focus from the beginning goes beyond COVID-19.’

The RISE-Vac initiative reflects the spirit of the Nelson Mandela rules, a UN document setting out the rights of people deprived of liberty, including the minimum standard of healthcare provided to people living in prison. In short, prisoners should be offered health services equivalent to those delivered in the wider community.

However, as the needs of people in prison are often high, and their prior contact with health services is typically lower than the average person, prison health may be the first sustained contact they have had with health services. This means that achieving health outcomes similar to those of other people may require additional attention.

‘The health needs of people living in prisons are complex,’ Dr Tavoschi says. ‘We see elevated rates of substance abuse, smoking, diabetes, cardiovascular risk, mental health issues and infectious diseases.’

From the perspective of individuals, and from a public health point of view, prison can provide a window of opportunity for linking ‘hard to reach’ people with services. While some prisons check hepatitis B status and offer vaccination where appropriate, immunisation services are not consistently available. RISE-Vac aims to figure out what works best and share this knowledge widely.

Building on pandemic experience

The rollout of COVID-19 vaccines was a test of prison health system infrastructure. The experience shone a light on attitudes to vaccination, revealing higher levels of hesitancy in many prison populations, largely driven by lack of trust in institutions such as the prison system, healthcare services and the state. Through focus groups, information meetings, and Q&A sessions with healthcare professionals, several prisons achieved significant results.

‘COVID has demonstrated that it’s possible to vaccinate at scale in prison, and this has heightened interest in expanding the vaccination offer in prisons,’ Dr Tavoschi says.

In some prisons, including the RISE-Vac partner in Lombardy, Italy, COVID-19 vaccination rates reached the same levels as those seen in the wider population. In the partner in Moldova, uptake in the prison was higher than the general population.

As the COVID crisis recedes, the project is returning to its original mission. ‘We are looking not only at COVID-19, but at other vaccines that are relevant across the life-course,’ Dr Tavoschi says. ‘Prison health services can propose vaccines based on the age or health condition of the individual.’

For example, HPV can be offered to juvenile offenders, people with diabetes might be prioritised for flu vaccines, and older people offered vaccines against flu or pneumococcal disease, in keeping with local immunisation schedules. Similarly, pregnant women, a key group for flu and pertussis vaccination, could have these vaccines integrated into health checks.

In the winter of 2022-2023, this approach saw some prisons offer COVID-19 and influenza vaccines together, in line with the policy applied in the wider community. Some prisons are now looking to build on this. ‘We are focusing now on cancer-prevention vaccines, hepatitis B and HPV, where there is a gap that must be addressed,’ she says. ‘Hepatitis B vaccine is available in some prisons in some countries, but HPV is rarely addressed at all.’

Life-course immunisation: including prisons in public health plans

As wider immunisation policy shifts towards a life-course approach, the Nelson Mandela rules imply the same thinking should be applied to prisons. Vaccination status is sometimes checked when people enter prison, presenting an opportunity for catchup vaccination. However, prison communities are not a homogenous population, so tailored approaches are needed.

Within prisons services, remand prisons ‒ where people spend a short time while awaiting sentencing or release ‒ have a lower average age than the prison population serving longer custodial sentences. Remand prisons in western Europe are also temporarily home to disproportionate numbers of migrants.

The challenge is not only to connect people with health services within the prison system, but to maintain care after release. ‘Continuity of care for people transiting through the system is a key issue in prison health,’ says Jemima Chantal D’Arcy of the UK Health Security Agency, a partner in RISE-Vac.

In some prisons, patients are supplied with three weeks’ worth of medication when they leave prison, but are responsible for arranging their own follow-up care. For prison services that operate an ‘active referral’ model, the prison health provider will book appointments with nearby health services or GPs, particularly for those with chronic diseases.

People in prisons ‒ and those with experience of incarceration who are living in the community ‒ can play a role as health advocates in marginalised communities. ‘We are working with lived experience organisations to help communicate about vaccines in prisons,’ says Ms D’Arcy. ‘This provides opportunities to build trust between services and the community, while allowing us as researchers to gain a better understanding of what it means to go through the criminal justice system.’

Future plans

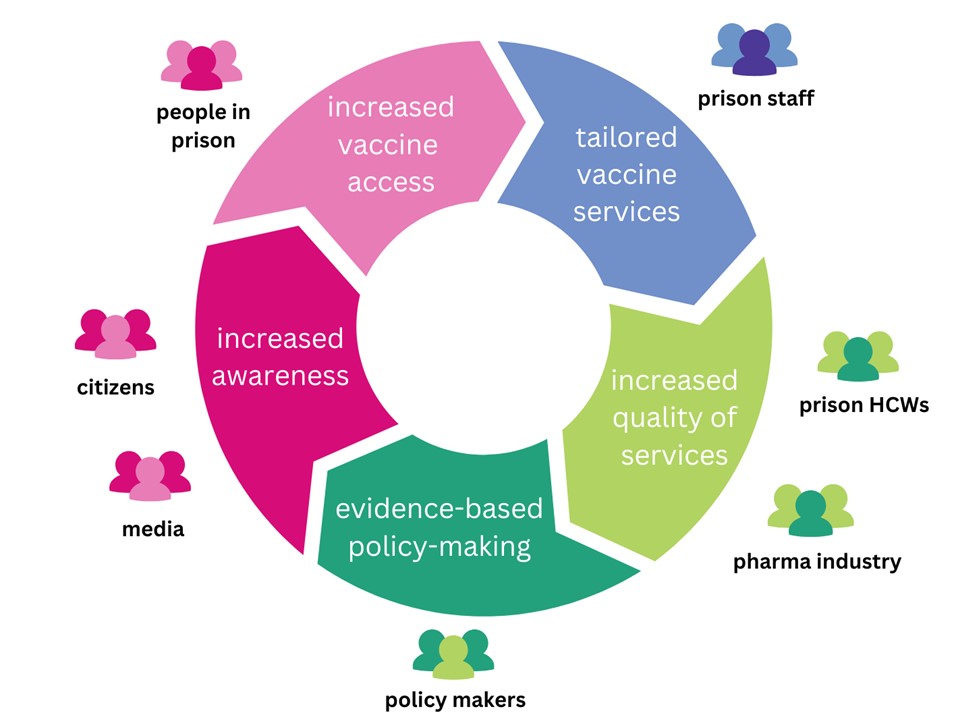

In the remaining months of RISE-Vac, which runs until the end of 2024, the researchers will collect evidence on existing vaccination strategies; develop information and training materials for people in prison (including staff); develop and test ways to deliver vaccines in a prison setting. The result will be a model for prison health which incorporates a life-course approach to vaccination that can be adapted and applied across Europe and beyond.